Home Lab

My home lab is where I play around with new technologies. I use the Tableflippers Anonymous infrastructure for more polished projects, but I use my home lab for internal things never meant for others, experiments, and such.

My home lab is really grouped into a few related, but distinct parts: My computer lab, my home network, my electronics lab, and my fabrication lab.

My computer lab is a 4 node Kubernetes cluster running k3s, each with 60-70 drives, 512GiB of memory, and 40 cores (80 logical) and a VM host running Proxmox with 1.5TiB of memory and 60 cores (120 logical).

The Kubernetes cluster runs Ceph with 210 OSDs and 740TiB of raw storage. Anything that can be reasonably containerized runs on the Kubernetes cluster and anything that needs its own OS or VM runs on the VM host.

I also have a backup host that runs Bacula to drive an LTO-6 tape library to perform backups of the storage cluster.

My home network has multiple core routers (NX-OS) interconnected with 40gbit/s fiber (QSFP+), and all other primary switches interconnected at 10gbit/s fiber (SFP+). The core routers speak BGP among each other, and also peer over an IPSec tunnel with the Tableflippers Anonymous infrastructure, AWS, and a few other smaller points of presence.

There are also 10 Ubiquiti wireless access points throughout my house that support approximately 120 or so client devices.

My electronics lab is where I do electronic projects and repair. It consists of mostly Keysight equipment but a handful of other brands as well. I have a few oscilloscopes, a couple of bench multimeters, a signal generator, a counter, a couple of adjustable DC power supplies, a DC load, a logic analyzer, a couple of microscopes, and a bunch of handheld tools as well.

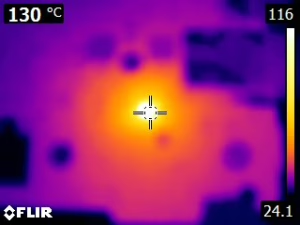

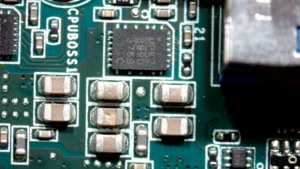

I’ve even diagnosed a failed component on an Intel NUC Mainboard. It turned out to be a capacitor that failed short. I diagnosed it by using my FLIR and microscope to identify the cap that had failed and then wicking up the solder and finally using pliers to remove the faulty component. Luckily it was a component that was not strictly necessary, and so after cleaning up the board, I was able to return the NUC to service in the house.

My fabrication lab consists primarily of a bunch of 3D printers, which I use octofarm and octopi on to drive. I primarily use it to print props for my D&D games.

Tableflippers Anonymous

Tableflippers Anonymous is a community of technically-minded gamers. In addition to the Discord server, we run several video game servers and other projects. We also run the Legion infrastructure these days.

The Tableflippers Anonymous infrastructure is a 20-node Kubernetes cluster colocated in Celito’s datacenter. Each node has 2x 10-core CPUs (400 cores total), 192GiB of memory (3.75TiB total), 2x 2TB hard drives (80TB total), and 2x 500GB SSDs (20TB total).

The nodes are each interconnected via a 10gbit/s cluster network, a 10gbit/s storage network, a 1gbit/s public ingress network, a 1gbit/s management network, two 1gbit/s unused networks for future expansion, and a 1gbit/s IPMI network. Each node also has IP-KVM connected to an Avocent KVM.

The nodes PXE boot a machine image off of a Synology TFTP/FTP server. The image is downloaded and extracted to a tmpfs root for the system rootfs. Each boot downloads a fresh image, discarding any changes to the tmpfs rootfs. The system image is based on Ubuntu and built via Dockerfile and then exported to a squashfs.

The first three nodes (as determined by static DHCP assignment) act as control plane nodes, running etcd, kube-apiserver, kube-controller-manager, and kube-scheduler.

Each node runs kubelet, CRI-O, ntpd configured to talk to each other, and CoreDNS for DNS resolution.

The Kubernetes cluster uses Ceph (via Rook) for storage, CRI-O for CRI, kube-router for CNI, MetalLB for LoadBalancer services, CoreDNS for cluster DNS, Traefik for ingress, external-dns and cert-manager for external name resolution and TLS.

An NX-OS based router speaks BGP to Celito’s router and advertises AS53546 and 144.86.176.0/23, my IP space. MetalLB allocates IPs from this range for type LoadBalancer services.

Legion

Legion Servers was a Minecraft server network. It is still online but is not being actively maintained. It consisted of several servers (or worlds) named “Legion of” something.

Legion of Anarchy was our main survival server. It was a never-reset anarchy server that took a vanilla-with-sprinkles approach to gameplay, had a 230GiB world without a border, and only two rules: use an unmodded client and don’t abuse chat.

Legion of Battles was a mini-game server running our own plugins that had several games: Tower Defense, kit- and classes-based arena PvP and PvE with a variety of win conditions (area control, survival, kill count, push-the-cart, boss-fight, racing) and groupings (free-for-all, teams, all-vs-one), survival games (both predating Hunger Games and then adapted to include fun mechanics from the movie). It operated behind the scenes on multiple servers that coordinated to dispatch battles, load worlds, and transport players to these battles and back. It also kept high scores and allowed for spectating battles.

Legion of Creativity was a plot-based creative-mode server that offered large plots on a flat world and had integrations to allow players to build arenas for the battle server and then import them into the battle system.

Legion of Destruction was a rapid-reset survival world with a small (~1k) world-border that had a scoreboard and was reset each week. Groups were scored based on the value of the collected items in chests near their bed. The group with the highest score at the end of the week was awarded a prize (and bragging rights), and then the server would be reset with a new random seed, and opened for the next week. The old map would be published in its final state.

Legion of Exile was our jail server. It was where people who cheated elsewhere were relegated to, but it allowed them to continue to interact with players as long as they didn’t abuse chat or try to technically break the server.

Legion of Legions (Nexus) was our hub server. This had portals to take you to all of the other servers and also had a bunch of fun easter-eggs. It was also where any server would send you if maintenance (or an issue) was occurring.

Legion of Parkour was an adventure server with a bunch of parkour courses built by our players on the creative server. It featured several parkour courses each with timing and leaderboards for fastest to complete each course.

Legion of Skyblock was a survival skyblock server that allowed players to start their own skyblock island or participate in groups.

Each server was part of the network, using clustered MongoDB for persistence of important cross-server information, a custom message-bus for exchanging real-time data between servers, and a ton of plugins built on top of these things: permissions, teleportation, chat, friends and groups, preferences, inventories, and a bunch of moderation and administrative tools.

The network ingested client traffic into an array of RoutingCord instances (a stripped down, minimal version of BungeeCord designed to handle multiple versions of the Minecraft protocol), which then forwarded traffic to a cluster of BungeeCord instances. The BungeeCord instances communicated with each other over Redis.

There were also a few other servers that weren’t part of the main server network, and were ephemeral in nature.

Legion of Forge was an ongoing modded Minecraft server that ran in seasons. Each season picked a modpack and was usually limited to trusted people who wanted to play. Interconnectedness with the main network was occasionally supported for chat, but not usually. Once the modpack ran its course, the server would be retired until everyone felt like a new one was in demand.

Legion of Vanilla was a temporary server that ran when Minecraft released a new version of Minecraft for the weeks before Legion’s main network could be upgraded to the new server. Sometimes limited connectivity of chat with the main network was hacked in depending on availability of tooling for the new version of Minecraft and demand.

Legion also occasionally ran other game servers as well, including Left 4 Dead, Factorio, Team Fortress 2, Call of Duty, Gary’s Mod, and BZFlag.

v1x1

v1x1 was a Twitch and Discord chat bot designed to help with chat moderation. It was written as a collection of Java microservices on top of Dropwizard with an Angular 2 web frontend.

Architecturally, v1x1 was built around an event-bus built on top of clustered Redis pub-sub and queues. Messages were ingested by the Twitch Message Interface and Discord Message Interface services, which maintained multiple concurrent connections to each channel for resiliency. Those messages were deduplicated on ingest and then passed to the rest of the bot’s services.

Channels were distributed and sharded across instances of the message interface services by using a multi-token hash-ring and ZooKeeper leader election. This allowed v1x1 to scale to handle more channels than a single connection could manage.

The message interface services were also responsible for translating between Twitch and Discord-specific concepts and generic v1x1 concepts so that the bot was cross-platform. There were even plans to add Mixer, YouTube Live, and a few other platforms to the supported platform list later.

Persistence was stored in Cassandra with proper consideration for eventual consistency and multi-node writes.

I even wrote a WebAssembly Virtual Machine in Java so that the bot could be extended with custom code. It wasn’t the most efficient VM, but it was a proof-of-concept and left room to optimize later.

Runetide

Runetide was my idea for a voxel-based mutable open-world MMORPG based loosely around the concepts in Minecraft. The world and quests was procedurally generated.

It is currently a paused project that never reached proof-of-concept stage because I just don’t have the time to engage with it right now.

Each character would have a class and race which would determine the primary abilities they would have, with options for cross-spec’ing. Each character would have resource pools of hit points, stamina, mana, hunger, thirst, and breath; attributes like strength, dexterity, constitution, stamina, magicka, and charisma; skills like fighting, survival, and magic; and special abilities.

Each entity would also have layered reputations between characters and factions like empires, kingdoms, guilds, tribes, clans, and settlements. Actions would impact individual and faction-based reputation for aligned factions, and this reputation would be used to determine hostility and friendliness.

There was a magic system based on a grammar of runes where players could customize spells by writing in the rune language. There was a potion system based on ingredients where the effects of the potion could be customized by the choice of which ingredients were used to brew the potion.

There was a settlement system where players could build up settlements of players or NPCs and level up the settlements into larger, higher tier cities, unlocking new structures and abilities. Settlements had mana pools that could be spent on settlement magic or settlement quests

Dungeons were pocket dimensions with entrances in the overworld with their own mana pool that an AI controller could use to reconfigure itself or use magic within the dungeon.

There was a vast pantheon with deities gaining power from how many followers they had, and could spend that power on divine acts. Each had their own domain and realm and boons for their followers.

Speaking of realms, the multiverse had several planes of existence, each with its own unique worldgen and environmental hazards. Planar travel was possible through portals or magic.

Architecturally, the game’s backend was built on top of ZooKeeper, Redis, Cassandra, and a Blobstore like S3 or Ceph. It was divided into microservices each responsible for its own narrow area of the game. Region servers were responsible for storing the world data, instance servers were responsible for managing entities, and so on.

Inter-service communication happened over HTTP and pub-sub topics. Each service had the concept of loading and owning a loaded resource, rather than reflecting changes directly into the database and using that for synchronization. This let the game keep active elements in memory of a service rather than contention on the database, and allowed the use of an eventually consistent datastore like Cassandra. Changes to these loaded resources were journaled to Redis for crash-recovery if a resource was not cleanly unloaded.

Client communication was done via Websockets and HTTP API. The client was never written beyond toying with a few different game engines.

ClueNet

ClueNet was a collaborative, technical community built around an IRC network and Linux servers offering shell accounts.

It started with two shell providers on ShellsNet, an old IRC network for Linux shell providers: chules.net, a provider run by Chris; and C&H Services, a provider run by Hunter and I. We all met on ShellsNet and eventually Chris decided to start ClueNet. chules.net and C&H Services merged and became ClueNet.

The primary components of ClueNet were a Kerberos realm and an LDAP directory for user and infrastructure management and an IRC network for chat.

Other than the central Kerberos realm and LDAP directory, the infrastructure was a bunch of older, consumer-grade machines on home Internet connections with hobbyists running machines and contributing what they wanted to the community.

ClueNet had a number of projects that popped up over the years:

- ClueShells. Free shell accounts on Unix and Linux machines for the community. It was integrated with the centralized Kerberos and LDAP user management to allow for SSO and user rights management.

- ClueMail. E-mail addresses @cluenet.org for the community. It was the whole suite of Courier services (esmtp, pop3, imap4), SpamAssassin, ClamAV, maildrop, and Squirrelmail.

- ClueVPN. A fully-connected mesh VPN written in-house to provide stable, static, private addresses for hosts otherwise behind NAT. It used a signed, versioned configuration file that was distributed via gossip, so centralized configuration didn’t need to be updated as long as you could connect to at least one peer.

- PHPServ. An IRC Services suite written in PHP. Offered nick and channel services, as well as advanced IRC bot services customizable with sandboxed PHP. It allowed users to write custom commands that invoked small PHP scripts to respond.

- ClueVPS. An evolution of ClueShells to offer Xen-based virtual machines to established members of the community.

- ClueWiki. A MediaWiki-based wiki serving as a website for ClueNet, as well as an archive of the old ShellsNet wiki. It contained documentation and posts by members of the community.

- DaVinci. An IRC bot that maintained a score of users based on how well their chatting correlated to a Clueful Chatting style guide.